Incentivizing Rental Housing Development Leads to Greater Affordability

Beyond the costs of providing rental housing, basic economic principles of supply and demand significantly influence its affordability and availability. Virginia has seen housing demand steadily rise, but we have failed to keep pace in delivering the necessary supply to accommodate population growth and increase affordability, particularly among lower-income renters.

The Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) estimates that Virginia is currently 550,000 units short of meeting current housing demand and needs to build another 30,000 units per year to match the state’s growth. The Joint Legislative Audit & Review Commission (JLARC) adds that the Commonwealth’s shortage of affordable housing units is around 200,000 units. Closing this imbalance between supply and demand is critical to addressing the Commonwealth’s rental housing affordability challenges.

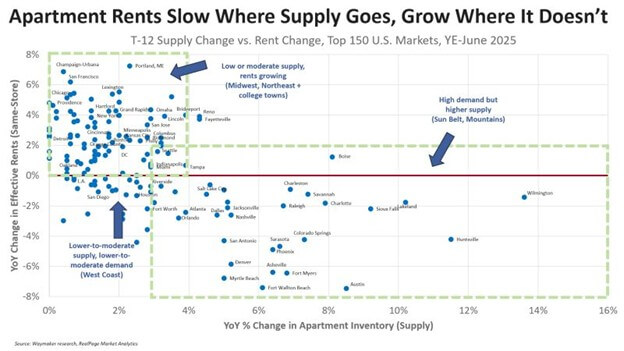

There is a strong correlation between growth in housing supply and rents. Rental Housing Economist Jay Parsons, utilizing data from Waymaker Research and RealPage on apartment inventory, created a chart in August 2025 that showed this strong dynamic in action. From year-end 2024 to June 2025, across the 150 largest U.S. markets, those that saw their housing supply increase by four percent or more experienced a decline in rents, while those that saw their housing supply increase by less than four percent saw an increase in rents. Parsons characterized the correlation as “undeniable.”

“No other variable – prior rent increases, incomes, affordability, home prices, employment, etc. – is anywhere near as correlated as supply. And this chart shows a clean correlation simply because we’re building so many apartments today that supply has outpaced demand.”

Source: Waymaker Research, RealPage Analytics

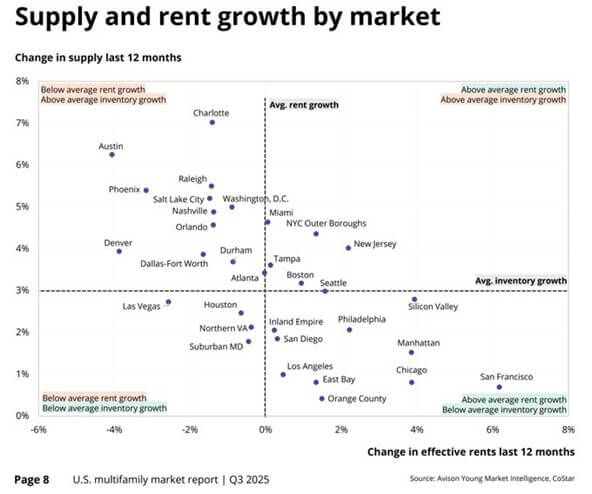

These findings are supported by an Avison Young Market Intelligence analysis of Costar data, released in Q3 2025.

Source: Avinson Young Market Intellegence, Costar

The Power of Filtering

This dynamic extends beyond mere correlation. A vast body of research demonstrates a direct correlation between increased housing supply and improved affordability in local housing markets. This is true even if only high-priced luxury units are constructed.

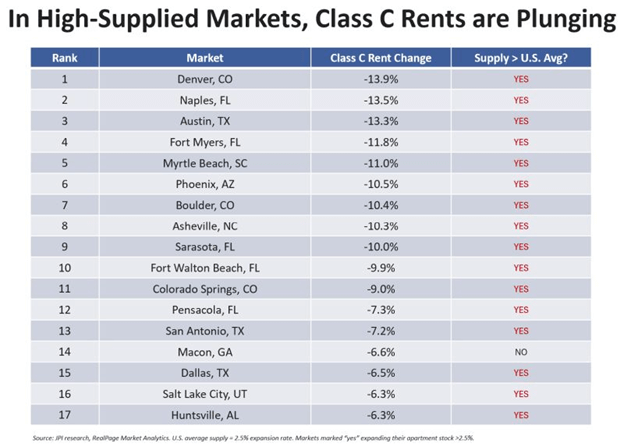

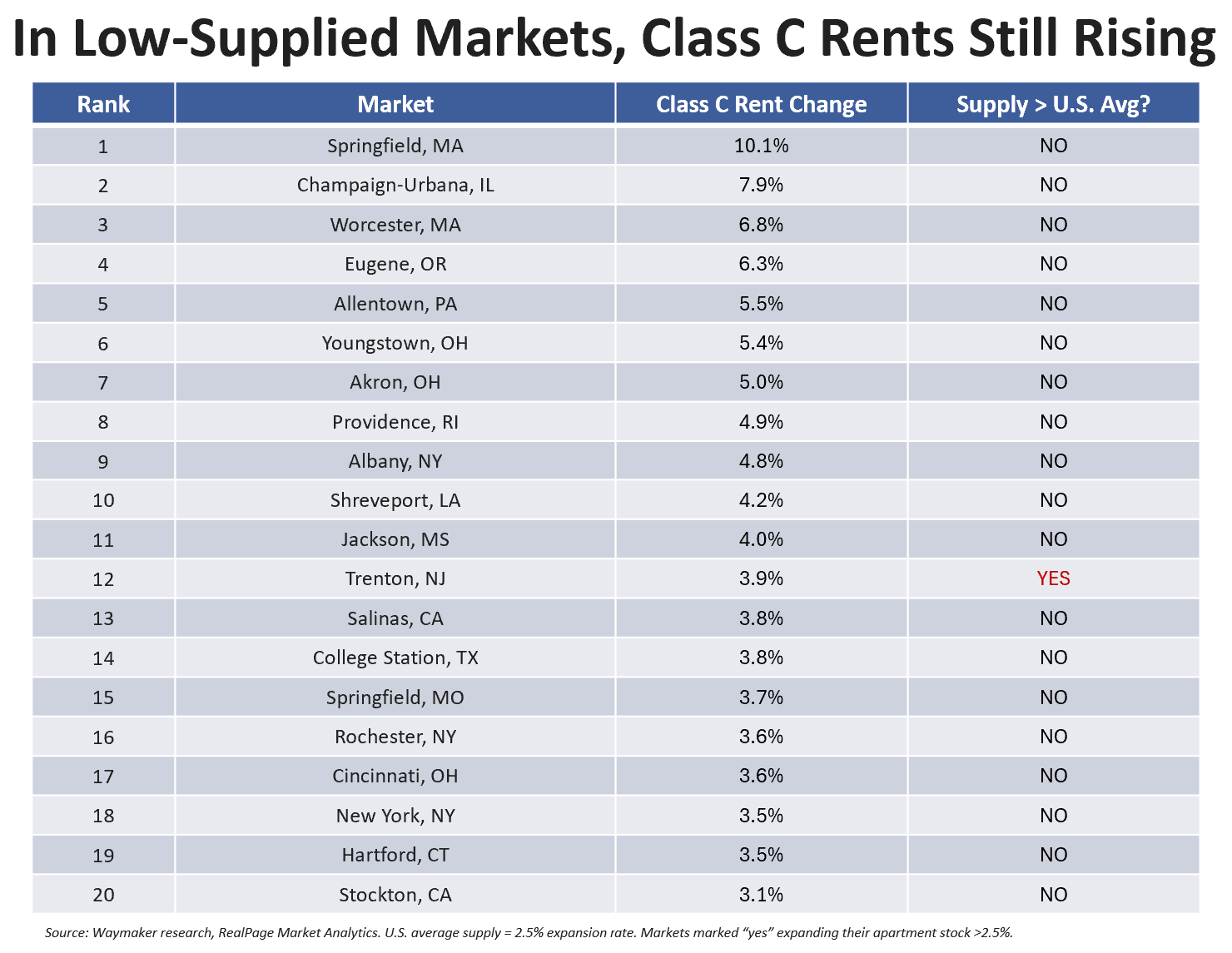

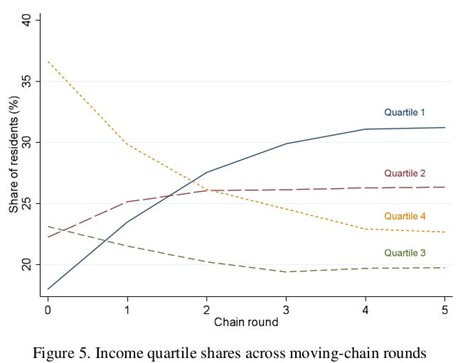

New construction does two powerful things. First, it moderates rents both within the immediate neighborhood where it is built and city/county-wide. Second, it results in a specific kind of housing mobility called “filtering,” in which households that can afford the new units vacate the existing, more affordable units they have been renting for more expensive ones. This movement frees up those lower-rent units for lower-income households. [1] [2] [3] The cycle repeats as other households vacate the even more affordable units they previously occupied, allowing households with even lower incomes to move into them. This process repeats as many as five or six times, so the addition of even expensive new housing units can benefit households at a variety of price points.

Source: JPI Research, RealPage Analytics, U.S. Average Supply = 2.5% expansion rate. Markets marked “yes expanding their apartment stock >2.5%, Change in Rents YoY through September 2025

Along with providing a vehicle for new households to enter the market, new market-rate supply reduces the displacement of existing renters. Households with higher incomes entering the market predominantly move into newer supply, reducing competition with existing renters renewing leases in their current units. Reduced demand helps keep rental prices for these units lower, allowing existing renters to remain in their homes at a price they can afford. Upzoning generally helps facilitate this filtering effect by allowing denser housing to be built in areas where it was previously prohibited, thereby increasing supply over time.

Source: Kindström, Gabriella and Liang, Che-Yuan, Does new housing for the rich benefit the poor? On trickle-down effects of new homes (April 18, 2024). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4890681 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4890681

Local actions and the need for statewide policy

Several localities in Virginia have attempted to follow these models to increase and diversify their housing supply. Arlington’s County Board adopted a package of zoning revisions in March 2023 under the title “Expanded Housing Options,” which allowed a limited number of small multiplexes within zones previously exclusive to single-family houses, provided that the buildings conform to the same outward structural limits as those houses and meet other requirements. Later that year, Alexandria’s City Council adopted its “Zoning for Housing/Housing for All” plan in November 2023 with similar rules to those in neighboring Arlington, and the City of Charlottesville adopted a new zoning code in December 2023 with similar provisions that included the elimination of parking requirements, which can be a costly expense for housing developers. All three of these codes have faced ongoing legal challenges.

In contrast, over the last several years, the Virginia General Assembly has placed a heavy focus on landlord/tenant law and eviction prevention, passing more than sixty related bills in the last five years alone. The bulk of this legislation has passed with the support of the rental housing industry, which has taken a proactive approach to codifying industry-best practices and directing assistance to residents to keep them safely housed. For example, during and in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, Virginia was a leader in applying federal funding for housing supports. The Commonwealth spent the entirety of its funding dedicated to the Rent Payment Program (RPP) in which housing providers and residents cooperated to make applications for the Department of Housing and Community Development to pay rent on behalf of unemployed residents.

However, in the years since, the General Assembly and Youngkin Administration have been unable to agree on funding for proposed rental housing supports, such as the 5,000 Families housing voucher for families with children in school, a program that AOBA has strongly supported. Moreover, these actions are tantamount to treating the symptoms, rather than the disease. Of the more than sixty housing-related bills passed by the legislature in the last five years, not one has targeted the impediments to new housing construction.

The Commonwealth’s approach to housing supply has largely been to leave supply action to local governments. Although seeking to respect local preferences, this approach has proven largely ineffective, and even when localities pass supply-side reforms, they often end up mired in legal challenges over technical disputes.

With 134 counties and cities, it’s too tempting for local governing bodies to express support for increased housing supply in principle, but condition their actions on neighboring jurisdictions acting first. Moreover, even when localities act, differences in specific requirements across the Commonwealth make it hard for housing developers to achieve economies of scale. Overcoming these barriers and fostering greater affordability will require state lawmakers to take the lead in establishing legislative and regulatory frameworks that promote increased housing development.

[1] Asquith, Mast & Reed (2023). Estimating the Economic Value of Zoning Reform. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w29440

[2] Bratu, Harjunen & Saarimaa (2023). City-wide Effects of New Housing Supply: Evidence from Moving Chains. Journal of Urban Economics, 133, 103528. Available at SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3929243.

[3] Mense, A (2023). Secondary Housing Supply. FAU Discussion Paper in Economics. http://andreas-mense.de/wpcontent/uploads/2023/01/SecondaryHousingSupply.pdf.