At Issue MD - The Inequities of Rent Control

The Inequities of Rent Control

Proponents of rent control often make a racial equity and social justice argument for capping rent. The theory goes that rent caps prevent vulnerable populations from being displaced.

Volumes of academic research exist evaluating these and other arguments in favor of rent regulation as an approach to affordable housing. Researchers have examined the deleterious impact of such policies on new development, property values, maintenance of existing housing stock, overall quality and supply of housing, tenant mobility, search costs, and even the failure of rent regulation to keep rent levels low.

In spite of this, rent control as a policy approach seems to be making a resurgence across the country. Rent control proposals have cropped up in nine states and hundreds of localities across the country over the last several years. Already in 2023, the Washington metropolitan region has seen rent regulation proposals in both Maryland and Virginia.

But new research from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and Johns Hopkins University sheds light on the inequities of rent control and its failure to benefit those populations it is generally intended to help.

The regressive outcomes of rent regulation

Rent regulation policies are generally designed with the intended purpose of reducing housing costs burdens for lower-income and minority populations to protect them from being priced out of the housing market. But case studies have shown that this does not necessarily bare out in practice.

Evaluating New York City’s longstanding rent stabilization policy, economists at Johns Hopkins University found that it has failed to produce the intended results. “Despite rent regulation being frequently promoted as an effective tool for housing affordability and achieving equality and social justice, we find that rent discounts are not progressively distributed. In other words, people with lower incomes do not get larger rent discounts. And many with high incomes get very sizable discounts.”

The study attributes this in part to larger market rent increases falling on those properties and communities that serve higher income populations. Therefore, they benefit the most from rent controls. Conversely, properties and communities serving lower-income and minority populations benefit the least. This actually serves to perpetuate rather than address wealth gaps among classes.

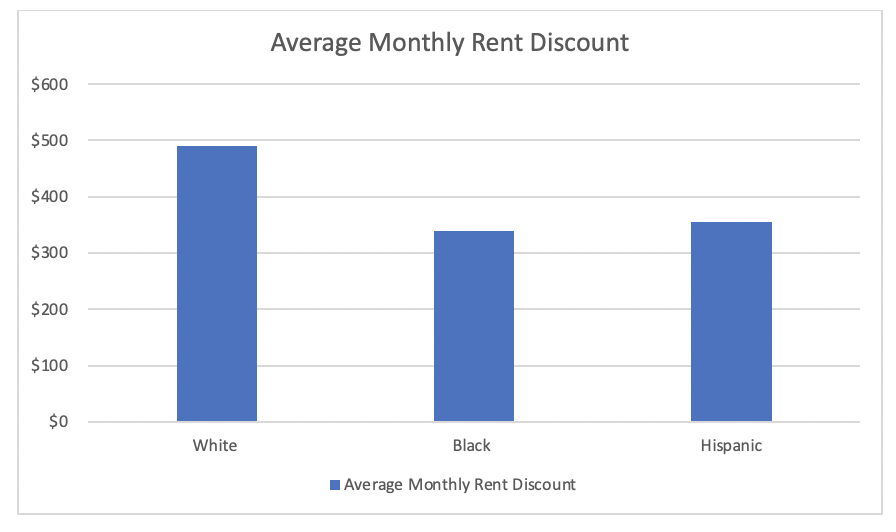

The unequal access to rent-controlled units also favors traditionally privileged groups, creating a particular problem for jurisdictions dealing with gentrification and displacement. The study found that access to and benefits of rent control are unevenly distributed across racial groups. Black tenants, for example, are 5% less likely to occupy a rent-stabilized unit than white tenants even after controlling for education, household size, and income. Average monthly rent discounts also varied by racial and ethnic lines.  The study attributes these gaps to a general lack of policy awareness across racial groups, length of tenancy duration, and potential housing discrimination.

The study attributes these gaps to a general lack of policy awareness across racial groups, length of tenancy duration, and potential housing discrimination.

Rent control subsidizes individual apartments and not renters, meaning that if a renter moves out of such an apartment, they forfeit the benefits. This incentive discourages households from moving out of a rent-controlled apartment, resulting in decades-long tenancies. Rebecca Diamond of Stanford University has quantified the effect of this incentive on housing markets, finding that rent control reduces the movement of renters by 20 percent. These extended tenancies effectively lock frequent movers and new renters out of the rent-controlled housing market.

Rent control actually redistributes wealth from lower income to higher

income populations

Studying the economic impacts of the recently adopted rent control measure in St. Paul, Minnesota, researchers at NBER confirmed the findings of the Johns Hopkins study. But they took a slightly different spin on the issue. Their research focused on the redistribution of wealth that resulted from rent control, looking at not just the demographic characteristics of renters, but also that of rental housing providers.

The stated goal of St. Paul’s rent control law is to improve the welfare of the residents of the city by reducing the burden of housing costs, especially for “persons in low- and moderate-income households.” Implicit in the goals of the policy is for the costs of rent control to be borne by rental owners, thus producing a transfer of wealth from higher income owners to lower income renters.

Using census data from property addresses, the study found that, in contrast to the stated goals of the rent control law, the largest transfer of wealth occurs amongst those renters who are relatively wealthier, while the smallest occurs amongst those who are relatively poorer. Like their counterparts at Johns Hopkins University, they found that tenants who gained the most from rent control had higher incomes and were more likely to be white, while the owners who lost the most had lower incomes and were more likely to be minorities.

Where rent control policies are more binding and more restrictive, the losses among lower income populations were greater. For properties with high-income owners and low-income tenants, the transfer of wealth was close to zero. Thus, to the extent that rent control is intended to transfer wealth from high-income to low-income households, the realized impact of the law was the opposite of its intention.

The rent control ordinance in St. Paul caused a transfer of wealth from owners to renters in the opposite neighborhoods as intended. Instead of wealthier owners transferring wealth to poorer renters, the wealth transfers were greatest when owners were relatively poorer, and renters were relatively wealthier.

A more targeted approach is recommended

Perhaps quite logically, a 2021 Stanford University study concluded that policies with higher default costs to housing providers lead to higher equilibrium rents, lower housing supply, and increased homelessness. Given the above documented failure of rent control as a policy approach to achieve the desired outcomes for lower income and minority populations, alternate approaches should be considered.

At Issue is compiled by the Apartment and Office Building Association (AOBA) of Metropolitan Washington, and is intended to help inform our elected decisionmakers regarding the issues and policies impacting the commercial and multifamily real estate industry.

AOBA is a non-profit trade organization representing the owners and managers of approximately 185 million square feet of office space and over 400,000 apartment units in the Washington metropolitan area. Of that portfolio, approximately 61 million square feet of commercial office space and 151,000 multifamily residential units are located in Montgomery and Prince George’s County, Maryland. Also represented by AOBA are over 200 companies who provide products and services to the real estate industry. AOBA is the local federated chapter of the Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) International and the National Apartment Association.

Along with input provided by AOBA member companies, the following data sources and references were used in compiling the attached report:

- Kenneth R. Ahern and Marco Giacoletti. Robbing Peter to Pay Paul? The Redistribution of Wealth Caused by Rent Control. National Bureau of Economic Research. May, 2022.

- Radio interview with Rebecca Diamond, Associate Professor of Economics, Stanford Graduate School of Business. “Why Rent Control Doesn’t Work.” Freakonomics Radio. April 3, 2019.

- Research Examines the Impacts of Rent Regulation and Implications for Inequality. Johns Hopkins University Carey Business School. July 21, 2022.

- Boaz Abramson. The Welfare Effects of Eviction and Homelessness Policies. Stanford University Department of Economics. December 15, 2021.

- Rebecca Diamond, Tim McQuade, and Franklin Qian. “The Effects of Rent Control Expansion on Tenants, Landlords, and Inequality: Evidence from San Francisco.” American Economic Review 2019, 109(9): 3365-94.

- The Impacts of Rent Control: A Research Review and Synthesis. Dr. Lisa Sturtevant, Ph.D. May, 2018.

AOBA strives to be an informational resource to our public sector partners. We welcome your inquiries and feedback. For more information, please contact our Senior Vice President of Government Affairs Brian Gordon at bgordon@aoba-metro.org.